Filter by Columns

Language is the same thing as paint. Sometimes you use it to communicate an easy message, easily. You don’t even need to describe what you’ve done because it’s right there in the picture, in the sentence. And sometimes you must use the tools you’ve inherited in funny little unsanctioned ways, and it won’t always make sense in language, what you’ve made, the picture a little abstract or confusing, because the language needs to do what it needs to do outside the boundaries of sense in order to indicate all the senses just beyond it. It needs to be funny or wrong, which is sometimes where you find more truth.

I have experiences outside of language all the time, and my job is to determine which ones are worth the friction of communicating them to another person, such as you.

My boyfriend is playing music in the other room. When he’s finished, his body emanates a kind of joy that can only be born from pure, pleasurable experience. No songs got recorded, no direct measurements of progress were taken. When he exits the room he is buoyant, and he smiles, and he carries himself like someone who doesn’t have to ask himself if he believes in the life he is living because his belief is deeper than thought, deep down in his bones, radiating outward and only eventually reaching his calloused fingers and exercised arms. “Muscled,” he will tell me to add when he eventually reads this.

I am sitting on an oversized purple chair thinking, of course, about language. When I think about language I write about language. But it comes up in less obvious ways, too. I think about poems or movies, and I end up writing about language. Or I watch birds fly to and from our house to our neighbor’s yard, and I end up writing about language. Or I try really hard to just be a gardener, to make something basic grow during the season in which it is fair to expect it, and I watch it tenderly, astutely, changing with the same rhythm in which I’ve come to expect the seasons to change, too—expectations nonetheless thrown by a warming climate—and when I finally sit down at the keyboard, having pretended I was taking my time to get here, I end up writing about language. I write about writing, a grad school ghost regrettably tethered to my posture; the way academia, when it shows up still in me, continues to conflate proof with love.

My new coach/therapist has me working with archetypes. And all my witchy friends are obsessed with crystals and stones. And I admit that I am someone who “has” an astrologer now, in addition to a boss and a doctor. So it will come as no surprise that I am surrounded by people with spiritual, magical reasons for talking about the “higher” or “lighter” frequencies and vibrations that show up in this universe, as well as their corresponding oppositions, whether it be in rocks or planets or fragments of our contradictory selves. And because I am a person who, no matter what I’m thinking about, ends up writing about language, it occurs to me that writing, too, has its light and shadow sides.

When I, the Writer, am at my best, I am full of passion for the challenge of grappling with language’s limitations. But when I, the Writer, am at my worst, lowest, weakest vibrations, the challenge of trying to put into language what one hopes is a life so rich and full that it expands beyond the constructed limits of words and their puny sentences leaves me feeling—to use a problematic metaphor—paralyzed. As if I might wish for the life to be smaller so that the words could at least catch up. So that the feeling of not being able to articulate an experience leaves me primed to be a victim of the world, mildly gaslit at all times as I accumulate experiences that I cannot describe. And so long as I’m down here squirming, I might as well make sure I’m not leaving any potential poems or essays behind, so that I feverishly look at the world not through the poet’s eye, but the publisher’s. Are you an essay? Is that an essay? Is there an essay here? Something I ought to grapple with and pull out and wrench through. I’ll teach you a lesson, I say beneath my breath, looking for something to write.

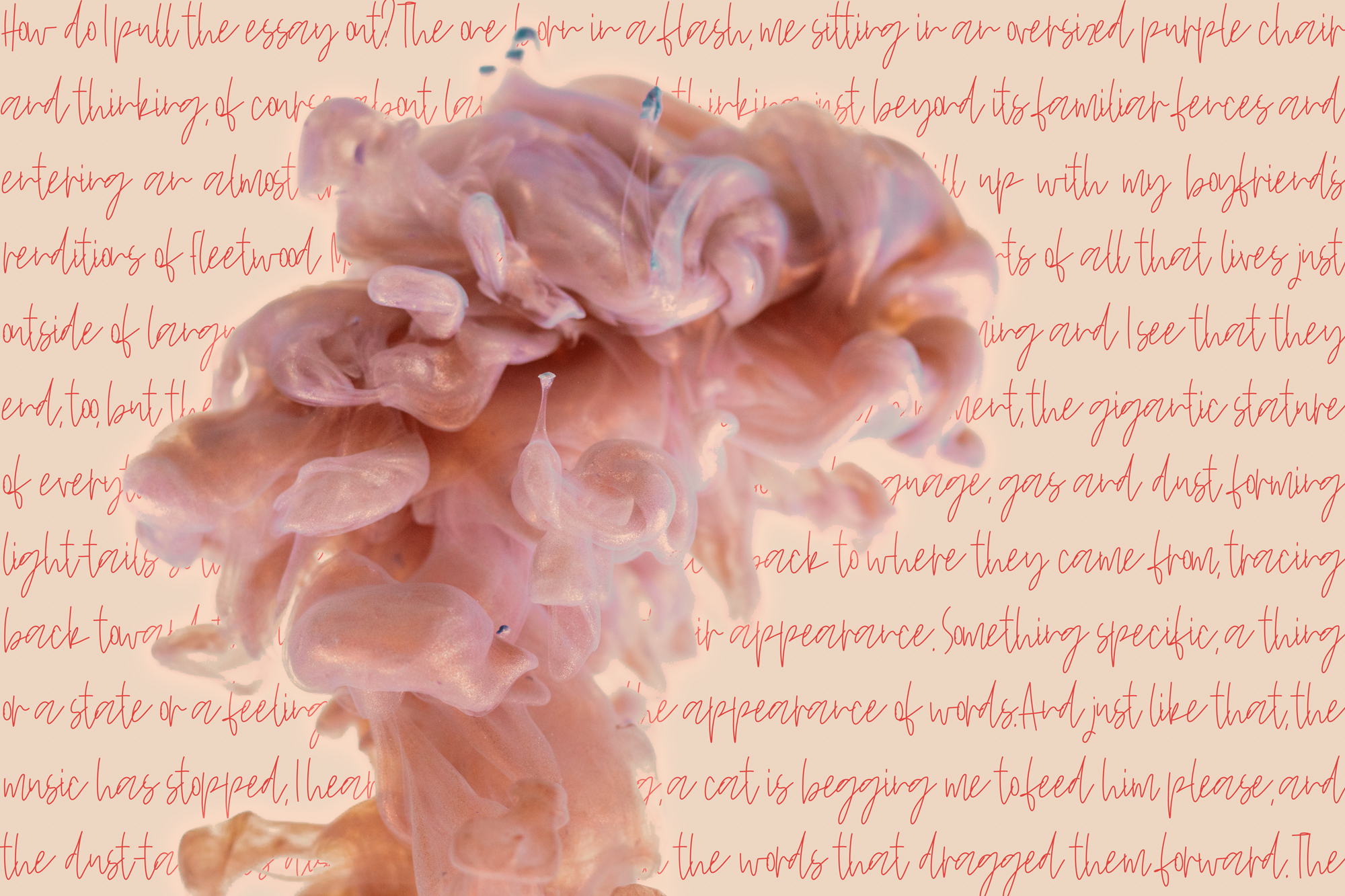

I start to feel as if I am a person whose head is made up entirely of essays, each region of my brain a topic, each synapse a word. If I said I’d like to open my mouth and show you my brain, it would be only a metaphor, but the Writer in me, still at her worst, is demanding that metaphors and poetic flourishes be balanced by reality’s grit: that I must also be capable of opening up wide enough to show you the pulsating, complex organ of me, at the very least my cortex just beginning to peek through and greet the sun. I am trying to tell you something that I would, like a good literary girl, very much prefer to just show you.

There are things that live within me, so real as to be beyond all requests for verification, and which I sometimes cannot bring out of myself and into the light of the world without changing them entirely. My brain being a prime example.

How do I pull the essay out? The one born in a flash, me sitting in an oversized purple chair and thinking, of course, about language, but thinking just beyond its familiar fences and entering an almost trance-like state, so that as my ears fill up with my boyfriend’s renditions of Fleetwood Mac and Dave Rawling, I begin to see figments of all that lives just outside of language’s proverbial grasp, I mean I see the words coming and I see that they end, too, but they come so fast that I also see, in this woozy-fuzzy moment, the gigantic stature of everything that exists in this world that is also not language, gas and dust forming light-tails so that the words momentarily reach back to where they came from, tracing back toward the incident that predated their appearance. Something specific, a thing or a state or a feeling, always predates the appearance of words. And just like that, the music has stopped, I hear the toilet flushing, a cat is begging me to feed him please, and the dust-tail has disappeared along with the words that dragged them forward. The essay had been a moment, a feeling, one that is now mostly felt, a moment before a moment ago. I did not pull it out in time.

That any writing manages to land on the page is a complete and utter miracle, a precise 50-50 mixture of blind dedication and random luck. I stand outside, neck bent back, tongue outstretched, waiting for the weather to change so that I may catch a snowflake on my tongue. Or a raindrop in my palms. Or some sunshine on my exposed shoulder. It is passive preparation, like gearing up for the season one season ahead. It is a certain out-of-touch-ness that masquerades as contingency. “It,” of course, is writing.

Are you often here too? I ask my partner now that he’s stopped playing music in the other room. Or do you feel more in control of coming and going from this space? My partner is also a writer, so we long ago normalized such conversations. “This space” is the one where language bleats.

I wouldn’t say in control, he says. But, he says, the less he writes and the more time he spends playing music in the other room, experiencing joy without the specters of proof or publication in his purview, without Academia awkwardly breathing down his neck, the less he cares about any of it. “It,” of course, is The Writing.

I am here all the time, I tell him. Joking about the notes I so often take in response to our conversations, even as I take notes now, in this very moment of speaking to him, a moment which will come to be experienced as nothing more than an essay that was constructed and edited and is now being read. A moment before many moments ago.

The best philosophers have died from this, my boyfriend reminds me. He takes a bite of an Impossible Whopper, a plate with a precise 50-50 mixture of french fries and onion rings balanced on the arm of his chair. Wittgenstein. Nietzsche. Not just the thinkers, but the writers, too. Kerouac, Hart Crane. We are slinking back down into the same conversation we have approximately two or three times a year, where we question and defend, and question and defend, in fervent turns, the various intersections between writing and suffering, between creative output and mental health.

This is not art! I am saying, thinking, writing. Am I yelling? I am writing but I am also not writing, another grad school trick/ghost. I am deep in my head, my boyfriend pecking me on the cheek—he has finished eating, my own food getting cold in the greasy bag—and reminding me to be nice to Sarah because he thinks she’s pretty great, and this business of watching birds and hearing music and being kissed by boyfriends only to end up writing about language means I’m thinking about writing about language rather than kissing him back. It means I cannot gauge a good essay from a bad essay from a non-essay from a bodily organ. It means the bird, whether I’m still watching her or not, eventually flies away.

Image artwork “Brain Text” by Ali Battey

Sarah Cook lives on the Oregon side of the Columbia River Gorge. She writes the monthly newsletter, For the Birds, and offers strengths-based editing & creative writing mentorship. Learn more at sarahteresacook.com. She loves rocks, bugs, and not smiling at men.

View all Posts