Filter by Columns

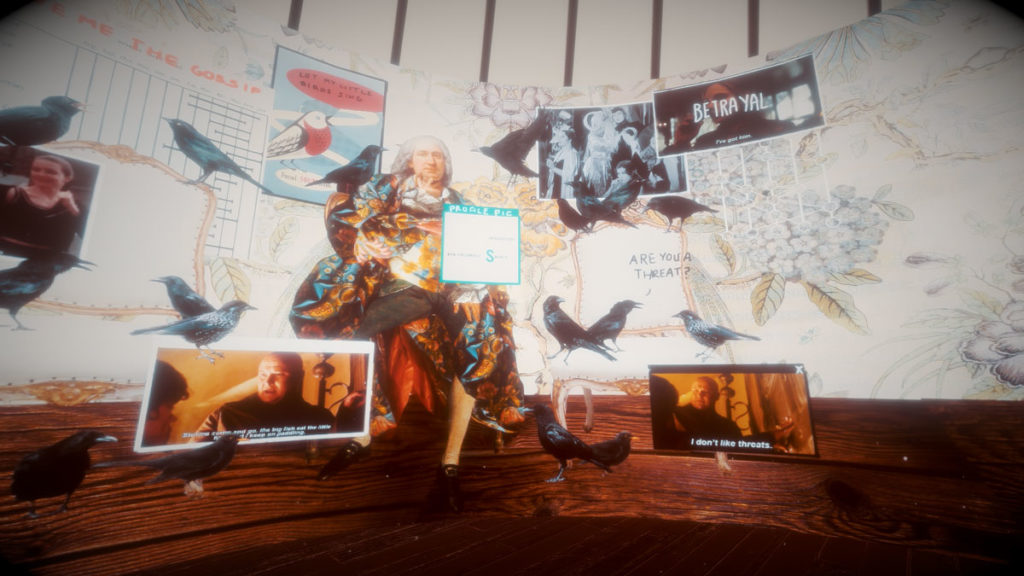

Backslide is a virtual reality experience for playwrights based on Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Its floating GIFs, semi-cryptic text, and witty play with classical and pop culture, invite the player to break linear thought. Backslide is a simulation and stimulation of the creative process.

In a traditional playwriting class, students often learn neo-Aristotelian scene structure and causality. As a writer and teacher of creative writing, I’ve always seen literature as a party game. Even if the endgame is serious, the participant is best served to enter in a relaxed state of mind, open to possibilities. To be overly goal-directed is to miss the value of play. The complex poetic form of the sestina was invented by troubadours amusing themselves with recombined line-endings at social gatherings.

My first attempt at an immersive experience was co-developing Anemone, a game in which a matrix generates random sequences of three panels that must be clicked when two from the same sequence appear, which then takes one into a field of text with a prompt. In assembling the heterogeneous assets, I was guided by the need for visual surprise and comic incongruity, as well as the use of high and pop culture in odd combinations, backed by a suggestive soundscape to disrupt standard patterns of thought.

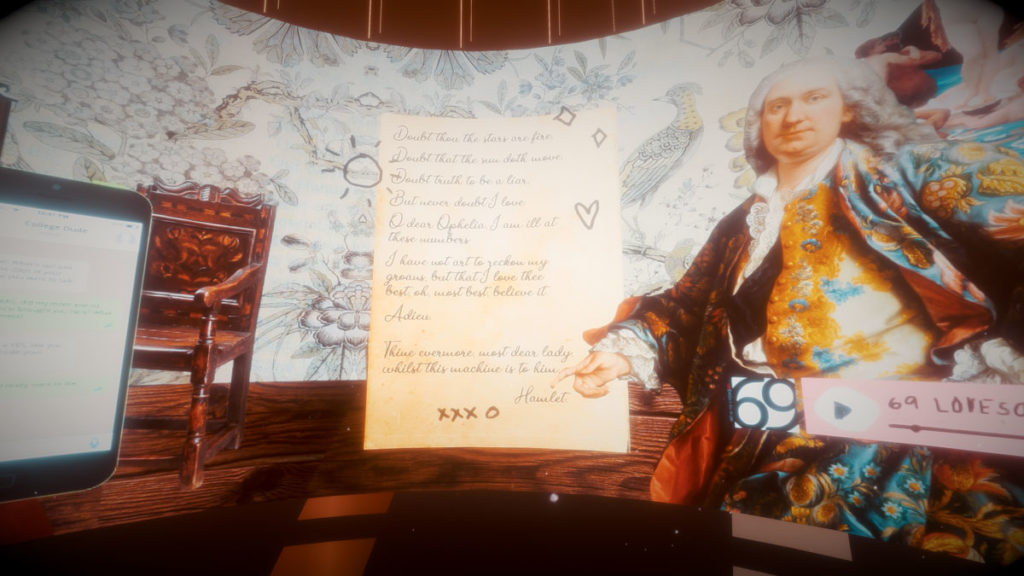

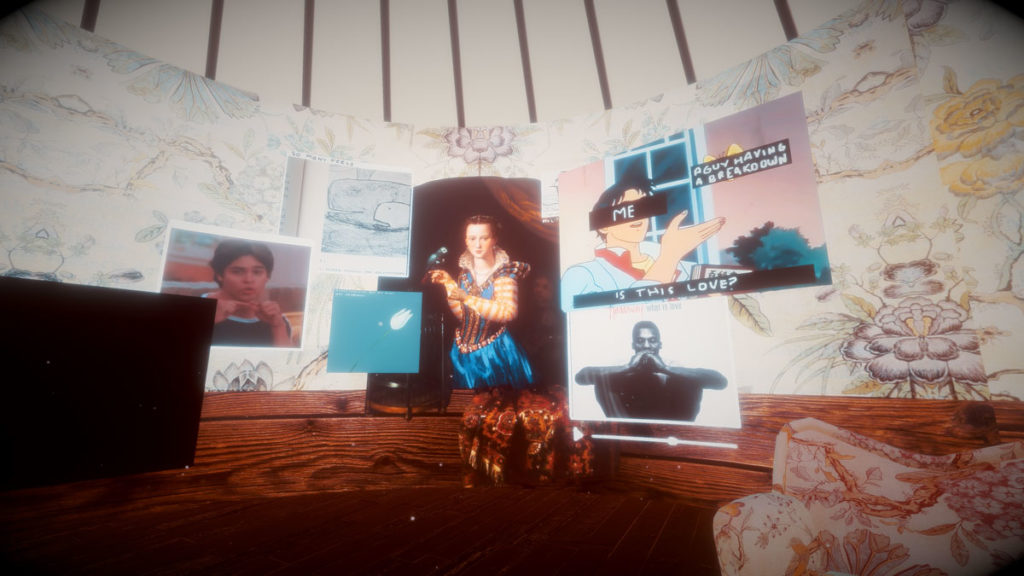

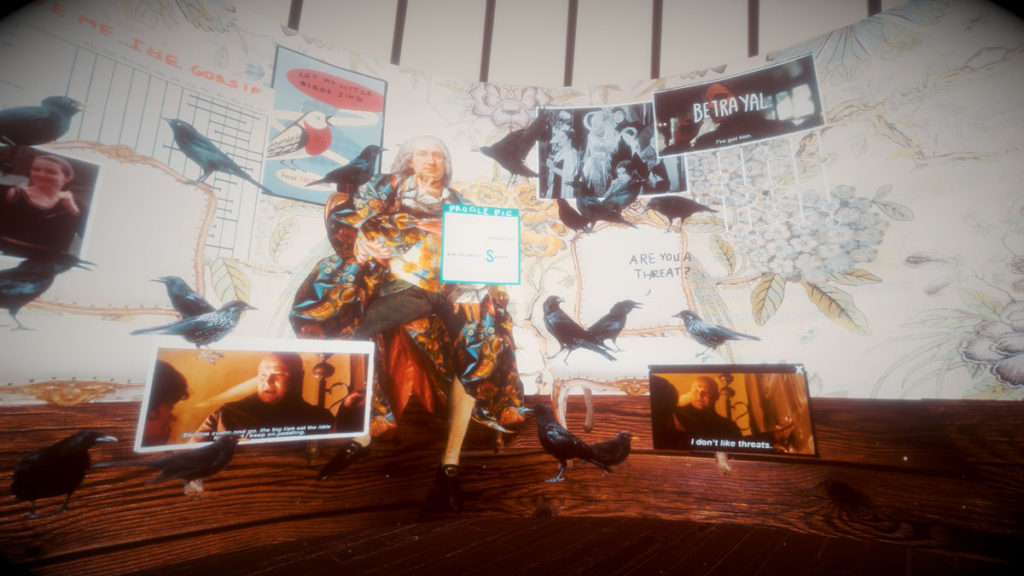

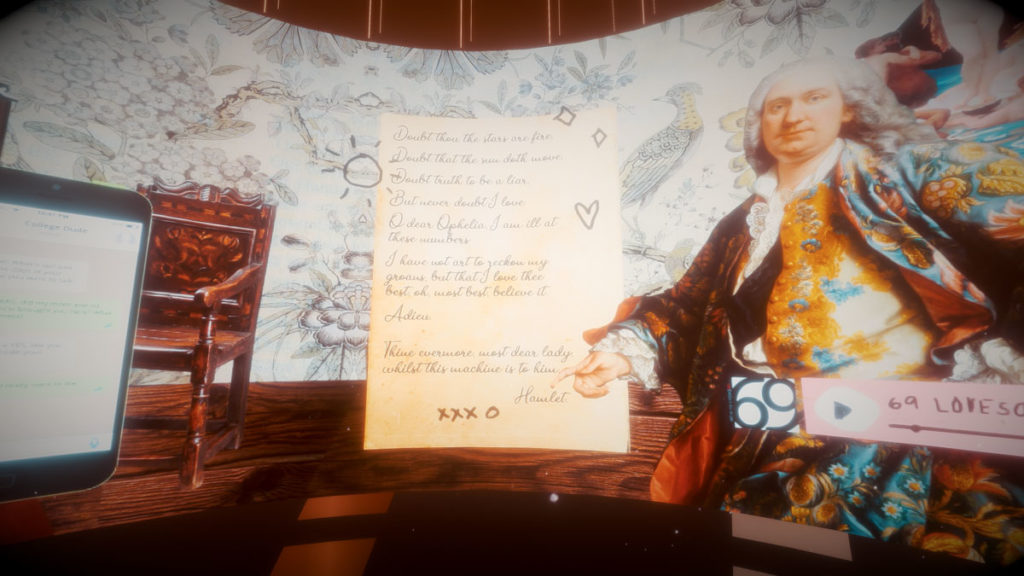

While working with Andy Campbell of Dreaming Methods Studio in England, and Mexican visual artist Nury Más in Mexico City, I conceived and co-designed Backslide, an immersive experience in sight and sound, navigable, to teach playwriting to creative writing graduate students. The project aims to break linear thought and move student artists into a more intuitive space. Backslide asks them to follow a plethora of visual and sonic stimuli, including witty pop culture GIFS and floating pages torn from Hamlet, in a perceptual reverie, to give way to a structured free association in order to draw on the less conscious part of creativity with greater efficiency.

In Backslide, the VR experience is a work of art in itself, a thing of beauty, conceptually complex⎯each of the rooms has a theme that the journeyer may pick up on with the right level of awareness, but like any work of visual art or piece of music, it offers itself differently to each person. Its visual field is simultaneously unified across the 24 rooms while offering great variety among them, packed with fragmentary textual clues. Everything you see, read, and hear goes together—or does it?

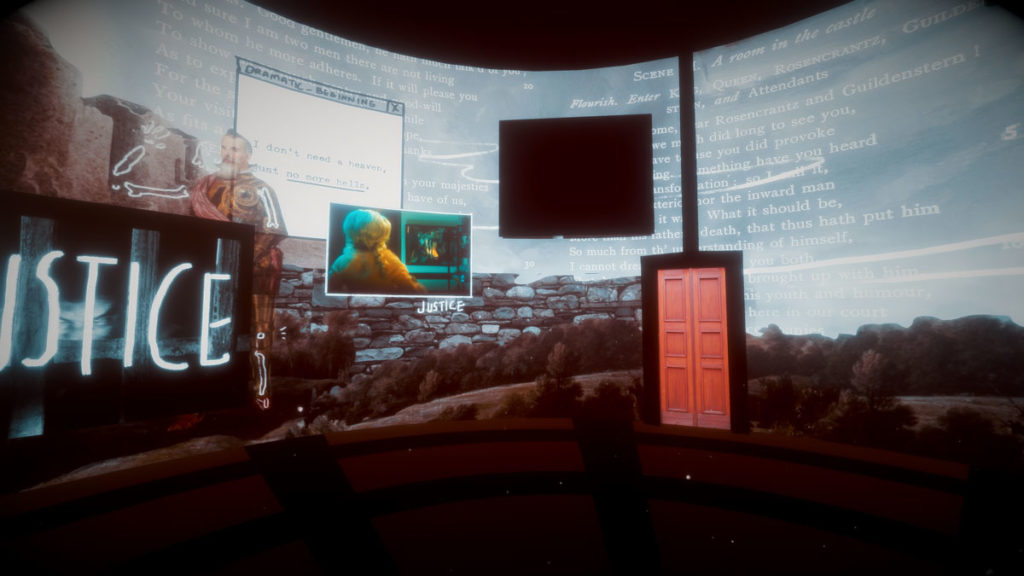

You enter through an immense, blue-hued rotunda. Saturated light and the echo of your heels as you walk reinforce the sense of being alone. You choose a door and pass through. Act One, Scene One features justice-related graffiti scribbled in the air, alongside Game of Thrones GIFs and other recognizable floating panels, some of which highlight and fly off to stick to the walls, like monolithic darts. The music in the background sounds somewhere between soothing trance and presage of horror. Down through the air float snowflakes, or pollen, or—some sort of radiation? Cosmic dandruff? The wallpaper, which Nury made by tearing out pages from an ancient edition of Hamlet, and a paperback of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, wrinkling some of them, and digitizing, provide texture, and a claustrophobic fullness in the spacious 360 of the room. Scraps of Shakespeare’s and Stoppard’s dialogue supply a metatext. Tarot card XI towers above, suggesting a fated outcome.

Prior to working on Backslide, I had produced and co-created Odyssey, an animated VR game for teaching long-form narrative poetry, with developer Kimo Oades. Like Homer’s Odyssey, it’s a journey that involves finding objects, traversing the Underworld, and killing the suitors at Ithaka with arrows. However, with Backslide, my thinking had evolved. I let go of the idea that VR had to mean gaming in the conventional sense. Instead, we focused on creating an immersive experience. You wouldn’t have to do anything except leisurely find the sequence of panels that would highlight and release you from the room when you were ready to go.

Rather, the point is to keep the student in the cyber-room for a relatively long time, observing, taking notes, pre-writing, until they grew satisfied or bored, as they assimilated the polyvalent field of meaning. Their pleasure centers should be stimulated, producing the dopamine that allows students to approach the arduous task of playwriting in a less stressed and more intuitive and even spontaneous manner. Yet the careful structure of Backslide as a whole, and its intimate connection to Hamlet and Rosencrantz, which we were studying, correlated this cognitive freedom to the rational rigors of the course.

David Ball’s Backwards and Forwards uses Hamlet as the prime example for learning dramatic causality by reading the play’s triggers in reverse order, to discover what leads to what. On the first go, students would write an entire full-length play backwards. It was something of a slog. The second time, students created a series of one-acts. Eventually, I realized that the point was for them to relax and feel in control—I am a bit of a method and structure freak, and I had to be sure to let them outside that borderline mania, reminding myself that the whole point of method, in this case, was to free their linear minds and let Backslide do its work.

As such, students utilized the immersive experience throughout the semester to write a series of ten-minute plays, in addition to two one-acts that weren’t related to the VR endeavor. The ten-minute plays were the entre-acts. That took some pressure off. I resisted student entreaties for me to overly explain Backslide. I told them to make of it what they would. They then got comfortable with taking from the experience whatever they wanted and doing with it as they see fit, just like the good old Dadaists. It was instructive to them, when we looked at their work later in class, deriving from the same cybernetic prompt, to see what different directions they took it in.

Below are excerpts from students’ reports:

Student One:

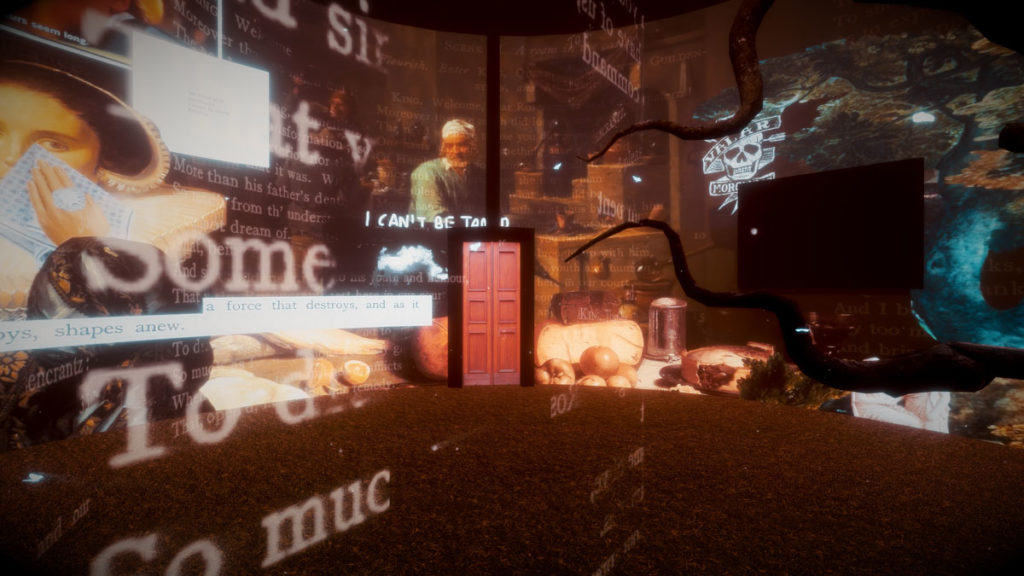

In Backslide Act IV the image that stuck out to me the most was the water, the flood, an ocean, or a sea so I wanted the location of my play to be in a forest by the ocean. I tried to incorporate as many words and themes as I could from Backslide, including the words/images psycho, the sea, dangerous, sailing, am I? Trees, flowers, mountains, missing, wine, boat, get help, now I am wearing a river and I have no escape. I wanted to portray innocence vs. evil in the Tommy character vs. the Father character and also wanted to incorporate an element of revenge.

These are the words, images, and phrases I wrote down while exploring Backslide Act IV: Godzilla, the sea, Psycho, dangerous, sailing, giant fish, we were sorry, so was I, wave, Am I? I wish I had enough poison for the whole pack of you, Are you ready? It’s happening, ugly baby is the only one to love, angry one the only one to hug, I told you so, trees, His head felt too loose, his body was stiff. He was cold. He didn’t move anymore. Flowers. This is my pain. Mountain. Feelings scaping your face. Stuck in an elevator. (And her list goes on.)

Student Two:

As I went through the VR of Act IV, one of the major themes that stuck out to me throughout as a common thread was death. Whether it was attempted or metaphorical, death was a dominant force. One bit in particular stuck out to me: “His head felt too loose. His body was stiff. He was cold. He did’’t move anymore.” I wanted to play with this bit the most, use it in my play if I could.

At first, I didn’t know what to write or how to work it in. I guess the first thing I figured was that it was going to be a murder mystery. The second thing I figured out – or I suppose my fingers and brain figured out – is that it was going to be an interrogation scene. From there, the play seemed to take on a life of its own.

Student Three:

This is what I saw in Act IV of Backslide:

The first scene is the danger room. Lurking, building, about to happen.

The first thing I noticed when I went through the door of Act IV was a man I assumed is Hamlet. He is wrapped in barbed wire to a drawing of an anatomically correct heart. The heart is numbered like it is part of a chart to teach students how to identify the different parts of the heart. There is grass and trees under Hamlet – he is not in the water that is in the rest of the scene yet.

There is an album cover for the band, The Flirts, greatest hits. I did some research and their most famous song is called Danger. There is a Borsch sea monster getting ready to eat a man with his hands up trying to defend himself. There is a Godzilla, that looks made of Legos, emerging from the sea.

I saw the temperature controls on a fancy coffee/espresso machine – boiling temperature, cranking/grinding pressure. There is also a bottle with a string wrapped around it and a lit match – something flammable must be inside of the bottle. Both these images invoke ideas of tension building – tension is almost to the point of exploding but not yet – like our dear Hamlet.

There is no question that once students habituated to this new concept in playwriting, they craved getting back into this offbeat virtual world to explore more of the many rooms. Andy made the experience compatible for Android phones, and Mac and Windows desktops, as well as for Oculus Rifts, despite the proprietary tendencies of tech companies and the ways they make it difficult for third-party apps to prosper. Having Backslide available on desktop, while it does rob the 3D experience of some of its drama, was important in terms of access. Some students are marginally tech-phobic and needed lots of reassurance and options. We made sure everybody had a version they could work with.

Backslide and immersive technology in general may serve future playwrights who want to break out of strictly realist modes of writing, while still honoring the prerogatives of storytelling. Once upon a time, the empty page was the trope of the writer beginning a new project. With the help of immersive technology, a simulated world, one that engages both rational and intuitive aspects of the creative mind, affords the writer a pre-existing process that is not about an emptiness to be filled, but rather a full, teeming artificial reality with which to engage, actively, en route to creating a personal theatrical vision.

All images provided by Johnny Payne

Johnny Payne is a poet, playwright, fiction writer, essayist, and poetry reviewer. His novel Vampire Girl, written to be read on a cell phone, will soon be featured in installments in The Ground Up. He has directed his plays Death by Zephyr, Los Feliz and Cannibals on Zoom. His most recent novel, Confessions of a Gentleman Killer, won the IBPA Gold Award for Horror in 2021. He has just finished a third book of poetry, Funeral Playlist, and is hounding magazine editors with its poems. Some of them listen. Payne directs the MFA in Creative Writing at Mount Saint Mary’s University.

Website: johnnypayne.com is currently shut down to be redesigned

Instagram: @johnnypayneauthor