Filter by Columns

A message on my phone from a friend across the globe breaks the narrative that the digital is toxic. Soft Systems explores technology’s plus side, its place in art, and grants access through the plate glass screens and into that which is worth embracing and corrupting.

My phone glows in my hand, the message beaming up at me puts a smile on my face.

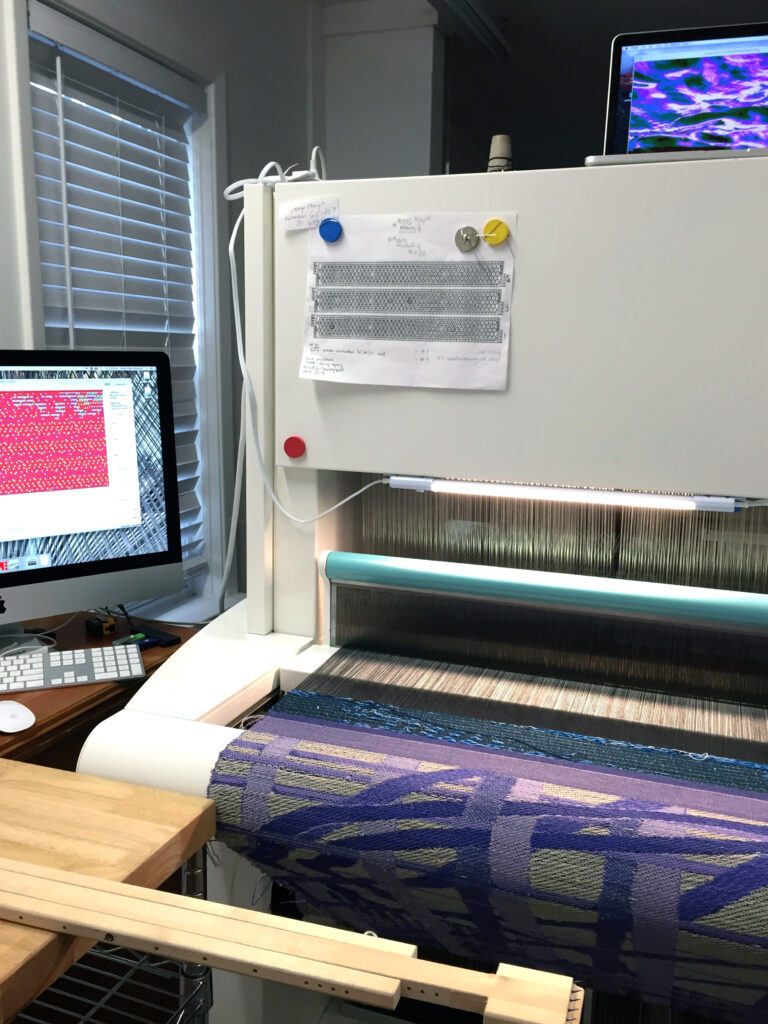

I’m in a small house in Ohio. It’s winter, the Cleveland clouds are looming, constant, and I am weaving. The creak of the floorboards are already familiar to me as I have spent every day for the past two weeks, from 10am to 10pm EST, swaying back and forth weaving. I throw wooden shuttles loaded with pink, orange, and purple threads, my wefts, to and fro through the black vertical warp slowly being dispensed by the loom. The process is calculated and hypnotizing. My feet are tired in their old grandma sneakers, but I only notice when I turn the loom off. When I return the next morning, I flip a light switch that connects the loom to power, I turn a band-saw style click-switch that enables a pneumatic hose, and then boot up the connected MacBook pro. All this tech to create tapestry.

I’ve come here from my home in Seattle specifically for this flow state, to break from my usual routines, and to have access to the illustrious Thread Counter Loom 2 (TC2 for short). Digital jacquard tapestry allows me to build narrative images in cotton and wool by controlling threads and their patterning to create recognizable symbols, illusions of depth and shadow, and text.

As I weave, I am physically and mentally submerged in the process. The TC2’s computer supplies my coded image that reads like an elaborate punchcard, lifting my warp threads to my precise design. The tapestry itself requires my activation: I must strike a foot pedal to activate the loom, advancing the warp a scant 3 millimeters and order the next arrangement of lifted warp threads. I pass shuttles, small wooden boats each holding a spindle of wound yarn, in a sequence of three colors, red, orange, white, red, orange, white, over and over again. My left hand shoots the shuttle through the opened warp, and my right hand catches it. My left arm pulls a bar towards me, compressing the weft. My right hand then throws the next shuttle back through the warp to my left hand. I pull the bar again, and I step on the pedal. Throw, pull, step. My machine and I count the rows. Each line of pixels is one weft thread across, and my images can require hundreds of wefts.

I seldom snap out of my meditation with the loom. When I received this text message from my friend however, my glee convinced me to take a break. Once I reply, I drink water, and find myself wondering if this interaction with the blue screen is bad for me. This message from a friend across the globe seems counter to the narrative that the digital is toxic. I grew up without the internet, without a digital life, and was the last of my friends to upgrade to a texting plan on my flip phone. Now I am a welcome user. A concerned user. An annoyed user. I ride the conflict in my personal life as well as my life as an artist.

I take my now-hydrated self back to the loom, restart its engine, and pick up the thread I had left off on.

I consider my role to be that of a storyteller, a collector, and as such it is only logical that I comment on my personal experiences. My world is technologically dependent, a relationship I cultivate with as much analysis as pleasure. I have so many machines: They act as books, as windows, and portals. As time goes on and my work develops, I find my desire for communicating ideas through pictorial means continues. I want to include the resource of information ever bubbling in my work, as it is a valid collaborator. Thus began my commitment to code, to practical applications of the digital, and to pneumatic, machine-based processes that toe the line between data and impression. My evolving into the world of the smartphone has been an experience of questioning, of pushing back and into.

I think a lot about the story tellers before me and the tools they used. In my own journey, I began my creative pursuits studying the process of printmaking. Intaglio opened my mind up to sensual materials like polished copper and pine resin, scary vats of acids, piles of cotton rags and layers of starched tarlatan. My hands were greedy for the goods, and scribing through liquid asphalt to create delicate imagery felt like power. I committed myself to learning every step of the process.

One day, as I was looking down at my hands, there was a distinct feeling of home I had developed specialized calluses from wiping ink off of countless hot metal plates; the blade of my right hand always shined due to this habit of friction. This printmaking technology, new to me but old to history, was typically a comfort. I felt a true material kinship; a hundred used exact-o blades, ink, and sheets of cotton rag paper dampened in books remain romantic in their possibility for image making. Closing my eyes, I can still feel the flow of the press’s wheel whirring as my flexing bicep cranked it. This machine, made in the early 1800’s, rubbed smooth by so many generations, was my collaborator. My support. Its tonnage used to commit a message from grease and carbon particles into paper. The whole room acted as a system in which to produce images in multiple, and my legs carrying me around in circles, my body bent over the glass tables measuring viscosity, my mind counting down the seconds, was equally vital to it.

While always obsessed with the print process, its result began to feel like a box. A carefully crafted etching was editioned, made into perfect multiples, and then framed behind glass. Impermeable, fragile, and cold. I struggled with the concept of paper, an old tool, and one that I almost hate to admit, was lessening in importance. I no longer kept receipts (scanning them with my phone), snail mail was a distant memory except for ads to grocery stores not in my area, I took notes in the cloud! How was I to commit to paper art, in its fragility, in its imported-from-Italy creaminess when I could not commit to it in my life?

The tension I felt between the life I had outside the studio and this entrancing methodology was fraught. The emojis, the text bubbles, the Facebook Wall (all shiny and new to me) felt like another world, futuristic and social. The rules of these spaces filtered into my prints occasionally, a slogan or keyword scribed onto a plate, but largely I was unable to connect my life in a busy city, my present, to my life with intaglio. I would sign off from my email, pick up a can of ink made from carbonized bone, and wonder ‘What year is it?’ As an artist I felt it was my duty to mark my experiences of the here and now, but felt stagnant. When I rebelled, cutting into my prints, pasting them onto walls, weaving them through found objects, I got closer to bridging the time gap, but part of my work was always rooted back to that old cast iron press. Pulling an artist proof, I found myself craving something less precious, less fragile. I would fight myself: ‘How can this technology tell my story? How do I convey the time I am living in through my work?’ Intaglio, while beautiful and satisfying, left me with a desperation for an update, a reboot, and distance from the lusciousness of copper plate. I was looking for a way into softness, into a material that could convey my messages with flexibility, flow, and warmth. I had to pursue a more inclusive tool to support my message.

Technology is an undeniable part of my life. In my work, I felt that there was no denying this presence of continuing information, the portal in my pocket, the relationships kept alive by SMS. How can I bring this reality into my practice in a way that spoke to their value? Their disruptions? How do I balance my phone with the view from my window? The warm blankets that surround me? I found an answer in the TC2, and the process of digital tapestry. Here codes, mechanics, and systems are all practicalities combined to create soft fabrics in cotton and wool, with incredible image-making potential due to modular thread combinations. This is a system worth embracing and corrupting.

When I came to textiles, and digital tapestry in particular, I stuck out my hand and made a deal. I came to the medium through a program offered while studying my MFA in Norway. I had entered the program there as a printmaking student, but as soon as the opportunity to try digital jacquard tapestry presented itself, I took it. I had never woven before, much less coded anything, but after three weeks of intensive theoretical exercise and one week of weaving, I was committed.

In this new world of textile, my machine-collaborator is from the current era. The laptop dictates a programmed binary plot graph to the loom, its specifications I coded based on my own digital paintings. It dispenses pliable cotton warp threads in the tens-of-meters. With every thread equating to one pixel, I feel the pull between the endless opportunity in the digital and the sturdy ground of the actual. I dance between limits. There is structure in the binary, a black pixel lifts a warp thread, a white pixel keeps the next thread at rest. For every section of my paintings, I select the binary pattern to reflect a certain layering of wefts and warps, similar to a ‘paint-by-numbers’. Certain patterns allow one of my three weft colors to come through, others show more warp. There are infinite patterns to build and explore, all with their own charm and texture. To save myself from too much potential, I usually float in a library of no more than fifty such options.

The tapestry I create is heavy, like upholstery fabric. When I run my hands over it, the various bumps and halos of fiber feel silky, fluffy, coarse. The yarn patterns optically blend to create unique colors, and the various thread patterns (satins, twills, tabbies) create a range of tones and dimensional effects. The images I create read a bit like etchings, with line and shade, density and dither, but in physicality they feel very different. Familiar, and soft, they fold and drape. They are inviting, and looking at them I get a sense of action.

As I become more familiar with the possibilities the TC2 possesses, I have begun to research the development of weaving technology. Woven textiles have existed for as long as humans have needed clothes; there is evidence of early people walking to North America, spinning fiber as they walked. The expansion of our species was directly supported by our development of textiles. I am enamored by the legacy of previous weavers and what those generations accomplished and contributed to expanses like agriculture, computer sciences, social identity, and so much more. Weaving is in everything. The soft and the hard, the flickering light of a tablet, the words we speak, the literal threads of our dressing. This revelation propelled my work backwards and forward in time simultaneously.

When I weave, I have the privilege to witness the early ages of human progress repeating at the core of my own actions. The looms I use, while being developed in the 1980-90’s are as connected to contemporary technology, literally being computer driven, are an evolution of the first punch-card driven technology made for weaving in the Middle East. I close my eyes and lean forward, my stomach pressing into the breast beam of the loom, and see the first two threads to have ever been crossed to create a structure. This same pattern, this moment in which a single fiber gains dimension, gaining strength, is one I repeat thousands of times in my tapestries. The crash of the past and present remains clear even as the modular TC2 loom, ever updating, hums before me. The teal and white monolith with its clean lines and silver-pin heddles holding each warp is a futuristic version of the original wooden frame laced with gut.

In my current phase of life, I do not view my digital self, my online actions and my off-line experiences as separate. I see myself participating in the legacy of technology, bringing it into my identity. My code is one of generations, my material is soft, transient, and evolving. When I create my translated images into tapestry, I am engaging with a chain of human technology. There is a pleasure in adding my own link in this chain, of channeling my life experience into a medium that is as legendary as it is innovative.

There are ways for technology to challenge us, to include us, to allow us to make gifts for our community. By quieting the voice that asks, ‘is this tool ‘good’ when our phone blinks up at us, and instead listening to the one that asks, ‘does this technology support me?’ we combine both halves of ourselves, the digital and the analogue, into one being. One being that is fully equipped, swaying to and fro, telling stories in layers of hand-dyed yarn, sharing stories to our people nearby and far off.

Allyce Wood is an artist living and working in Seattle, WA. Through the use of digital and handmade processes, Wood makes installations, works on paper, and textiles with a focus on digital Jacquard tapestries. A collector of technologies and threads, of language and codes, every process tells a story of a different method of reckoning. Punchcards and watercolors are as vital as the keyboard on her outdated MacBook. This passion for systems, for breakable rules, stems from a lifelong curiosity of reason and rule-bending.

Wood has been published in Subjectiv Journal (Portland), Fuck What You Love (Glasgow), and Equilateral Thoughts (Oslo) and other US and International publications.

Website: https://allycewood.com/

Instagram: @a11yce