Filter by Columns

09.15.2022 |

Non-fiction

The Zen master and poet Eihei Dogen wrote an essay called Uji, Being-Time, which is essentially, about the non-separation between being and time. They are one in the same. Being, as in action, is time, and time, being. The totality of all phenomena rests in the present moment, which contains both past and future. Andre Breton defined surrealism as “…in the absence of any control exercised by reason…” Both of these thoughts influence my art, writing, creativity, overall being. Kodo Sawaki says, “It’s impossible for us to see the true nature of reality…Here, all is an illusion. In everything in the world there exists nothing besides illusions…”. Poetry and prose are my ways of attempting to convey my experience with true reality. Exploring these elements, I am able to better understand my own traumas and experiences of isolation, otherness, and crisis. These deep inquiries allow artists to have wider perspectives and keep an open mind to different possibilities and experimental leaps. This essay about Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month is an attempt to talk about my cultural experience and identity, while at the same time conveying identities are beyond what we believe to be true about identities. There are three generations in this essay, all of whom are the same, yet a different person.

Treading along in this dreamlike, illusory realm,

Without looking for the traces I may have left;

A cuckoo’s song beckons me to return home,

Hearing this, I tilt my head to see

Who has told me to turn back;

But do not ask me where I am going,

As I travel in this limitless world,

Where every step I take is my home.

13th century Zen master and poet Eihei Dogen

I was thirteen when I was first arrested. Detained. Humiliated. Treated as if I already hit puberty. At thirteen I still carried my baby fat. Just had my braces removed. Had a collection of Pokémon cards. At thirteen I was lost in different cultural identities. I knew my father was a drug addict. I knew my mother was from another country. I knew what it was like to play all-stars in the local baseball Junior League. I knew what it was like to be abandoned at a casino entrance because the neon lights were too strong of a temptation. I knew that both parents, at some point in their lives, understood the experience of a jail cell closing behind them. And yet at thirteen, no one knows anything.

When I was in eighth grade, my father was mis-diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease. He had a mental breakdown. We spent most of the school year living out of motel rooms in the central valley. We were hotel hopping and I had to resort to completing my homework on motel stationary notepads. Meanwhile, my mother was by my grandfather’s bedside 200 miles away off the coast of Monterey Bay as he was dying from cancer. By the time she returned, my father had disappeared. The summer before I entered high school, my mother decided that I was to spend a few weeks with my aunt, uncle, and cousins just south of Salinas. During the train ride south, I was detained by a SWAT team in Richmond, CA. They mistakenly thought I was transporting kilos of cocaine. They treated me as if I were old enough to deploy to war or have children of my own.

Two other critical experiences shaped the rest of my life at this time: I began using drugs, and I discovered a Buddhist book on my mother’s shelf. It was an old hardbound from a collection of other religious material. It was beige, tattered, and only read Buddhism on the cover, which was all I needed for it to feel relatable. The Buddhist text anchored me just enough to my Asian roots to keep me exploring the teachings while at the same time chasing the dragon. In some ways the opposites counteracted one another. But junkie and criminal are easily defined terms that my prepubescent self attached to because it was easier than attempting to define a multicultural identity that often kept me confused and self-conscious. Once drugs entered my life, more arrests followed. I was already deemed a criminal threat and my anger and humiliation from the traumatic event convinced me to prove to the world what they already labeled me as. I couldn’t sit with my ambiguous identity when I could easily tell myself and others I was simply an addict.

“To study the Buddha Way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be actualized by myriad things. When actualized by myriad things, your body and mind as well as the bodies and minds of others drop away. No trace of enlightenment remains, and this no-trace continues endlessly.”

Since the pandemic and spread of all the seemingly endless COVID variants, my mother and I have gathered at my obaachan’s house in Marina every May, which just so happens to also be Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month. Though it was perhaps just a coincidence, my mother would say otherwise, that a higher spirited reason brought us together. When I was younger, she would ask me why I chose her and my father as parents. Growing up I was never really aware of any month dedicated to us. My mother and uncles attended Japanese festivals, like Obon and Omizutori, both in Japan and once they moved to the U.S, but the next generation not so much. It wasn’t because we didn’t want to, but because my mother and uncles struggled with their own multicultural identities after moving from Japan, where their only family and community members were. My mother was closer with her father and my uncles closer with my obaachan. In Japanese tradition the boys are usually favored and this led my mother and obaachan to have a disintegrated relationship. This, compiled with being treated as other, subconsciously led my mother to identify more with her American side rather than her Japanese side.

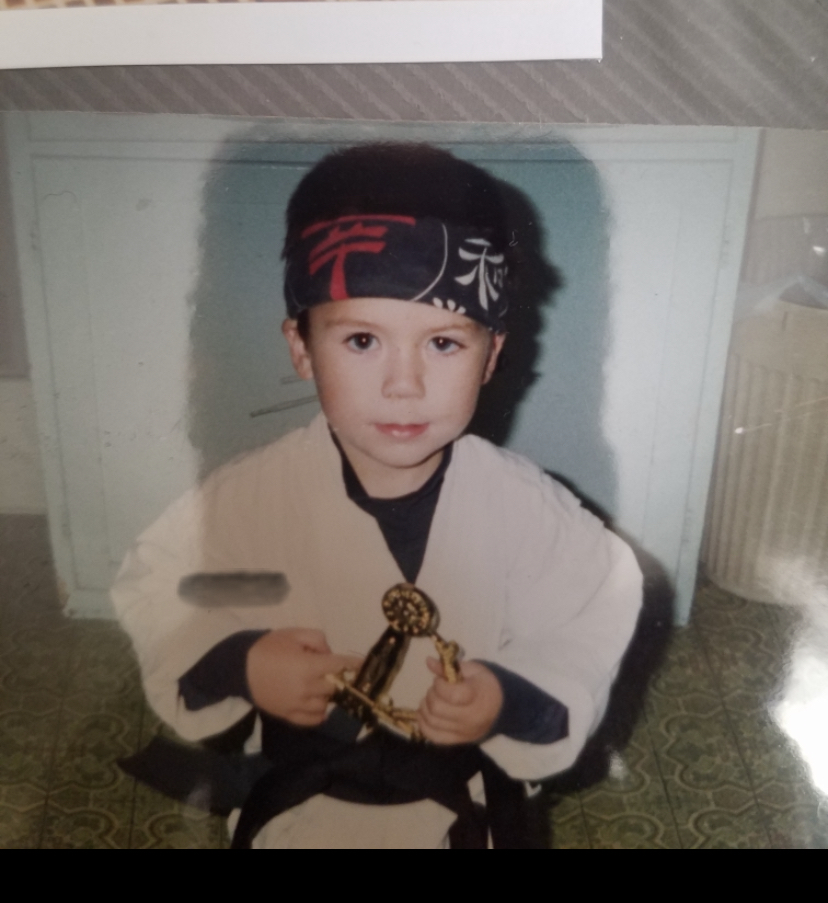

My cousin, brother, and I would have embraced and benefited if we had more of a Japanese American community in our lives. We were avid manga readers, anime watchers, karate students, natto eaters, Pokémon card players, and Gundam Wing model makers (we were what people think is cool now but thought were weird and strange back then). Not to perpetuate stereotypes, but we really were into all of these and felt a closer affinity with our roots because of the kanji lettering on the packaging and Japanese speaking characters and forest spirits in My Neighbor Totoro or the shape shifting tanuki in Pom Poko. The kanji on these packages resembled the symbols and art my obaachan had in her living room, a place of refuge.

I remember holding these anime VHS’s, looking at their covers, and feeling like the image was meant for me: imaginative surreal landscapes with characters that represented my facial features. At school, there was a popular racist playground rhyme that goes “Chinese/Japanese/dirty knees/look at these”. When someone says Chinese and Japanese, they pull their eyes back to slant them. I remember being subjected to this cruel teasing. While I immersed myself in a world where Japanese American street fighter Ryu dominated the fighting tournaments while also having moral and ethical values, these hurtful rhymes couldn’t hurt me because I had a hero to look up to.

“When you ride in a boat and watch the shore, you might assume that the shore is moving. But when you keep your eyes closely on the boat, you can see that the boat moves. Similarly, if you examine many things with a confused mind, you might suppose that your mind and nature are permanent. But when you practice intimately and return to where you are, it will be clear that there is nothing that has unchanging self.”

A few months ago, I visited my mother, uncle and 90-year-old Hokkaido born obaachan in Monterey, California, a small coastal town where my brother and I were born. My obaachan’s house is the only stable, constant home I’ve known since birth with its sand dunes, beached seal colonies along the wharf, and abandoned military barracks. In 1974, my mother began high school, which was also six years after the term Asian American first made the scene in Berkeley from Asian activists and the year before Bruce Lee’s masterpiece Enter the Dragon premiered.

When I was four my family moved to Sacramento, which felt like an insurmountable separation from the windy coastline stretching from Moss Landing to Ragged Point as well as my Japanese heritage. My father was from the outskirts of Sacramento, but my mother had no connections or community there. They had a tumultuous relationship and my mother was always attempting to keep an on-again-off-again marriage together. Their relationship held a complicated history of incarceration, drug addiction, rehab and affairs. My mother has always fallen for damaged men with low self-esteem. Big hearted but injured human beings. This being a by-product from her tumultuous relationship with her mother. In Japanese culture the boys are always put on a pedestal and the girls are always burdened with higher expectations. Though my uncles could do no wrong, my obaachan held a magnifying glass to my mother.

My obaachan learned English as a second language and my grandfather didn’t like Japanese spoken in the household with the children. Even within her very small community, she was quite isolated, an effect from a combination of culture shock and trauma from growing up in a war torn country coupled with my grandfather spending most nights at the Legion Hall. My obaachan and my mother didn’t understand each other. It wasn’t until recently when my mother read Ruth Ozeki’s The Face in the Mirror and watched an Amy Tan documentary when her childhood began making sense. She learned of a shared experience with Tan and her mother and realized why my obaachan acted the way she did. After watching the documentary my mother began to let go of resentments she’d been carrying for decades. My mother could see the pressure my obaachan faced with raising Japanese American children. Sometimes we need to see someone else’s struggles to come to terms with our own. My mother was a wild child and my obaachan didn’t know how to teach my mother that society didn’t consider them as Americans, but perpetual foreigners. We always had eyes on us and an unlevel playing field. Hearing this, I tilt my head to see who has told me to turn back.

My genealogy looks something like Bruce Lee’s, which I have been called three times this year alone while randomly walking along the street. I’m more Japanese with ancestral roots of Ainu than anything and identify as such, and Swedish from my father’s side. I am also Ukrainian/Slovakian, Northwestern European/French and a small percentage of Balkan. I look exactly like my mother and my brother looks like my father. People have often described my looks as ambiguous, a term I’ve heard many times growing up. For a long time, I have been defined by what I am not instead of what I am. As a child I knew in my bones I was Japanese and felt closest to my mother. As I got older, my connection to my Japanese side weakened. My friends who were Asian seemed to have had a stronger connection to their cultures of origin, their family, and their stable living environment—three elements missing from my childhood. My first identity marker as a teenager which I felt truly connected to were drug addict and criminal, which complicated my identity further, without looking for the traces I may have left.

It’s contradicting and confusing that America has a single month dedicated to different ethnicities, most of whom walked on American soil prior to its common-known discovery and whose participation in building the country are still left out of history. What’s especially perplexing is the month dedicated to those who were already here. For example, the homage month to “American Indians,” as if that’s an equal solution to acknowledge the conquering and genocide of people who didn’t conform to white settlers’ hell bent on taking over this land. Another problematic factor is the name. The struggle Pacific Islanders face is more in line with Indigenous struggles than the Asian American struggle. Though we may share similar features and stand in solidarity with one another, it doesn’t mean we have the same history of displacements, culture and colonization.

“When the myriad dharmas are each not of the self, there is no delusion and no realization, no buddhas and no ordinary beings, no life and no death. The Buddha’s truth is originally transcendent over abundance and scarcity, and so there is life and death, there is delusion and realization, there are beings and buddhas. And though it is like this, it is only that flowers, while loved, fall; and weeds while hated, flourish.”

During May in the first year of the pandemic, I finished my undergraduate studies and was accepted into an MFA program for Creative Writing. I also successfully created a formerly incarcerated students club on campus and built a community of support for those with an incarceration history. With the first semester experience on Zoom finished, the highways clear of travelers, and a recent degree earned the year I was turning 30, my wife and I drove from Humboldt to Monterey to escape the claustrophobia caused by the lockdown. Subconsciously, I was worried there was a possibility this was my last chance to see my obaachan. In times of stress I am always relieved to return to my hometown. Like in Dogen’s poem, there is a calling adrift in the central coast wind but do not ask me where I am going, as I travel in this limitless world, where every step I take is my home.

We took all the precautionary measures when we arrived at my obaachan’s doorstep—wearing masks, social distancing, our hands dripping in sanitizer and speaking to each through a screen door. My obaachan, who survived two atomic bombs, food shortages, extreme violence in military occupied Okinawa, and a highly strained racial environment in Atlanta in the early 70s, sternly, but politely, opened the screen door and embraced me before we left. Her warm hug had me paranoid for a few weeks and checking in on her constantly because of the possibility of transmission. We didn’t spend much time together that day but was left with her yelling out I was her most handsome grandson. I’d be lying if I said part of the trip wasn’t to hear that endearment in person. You’re so handsome, three words from my obaachan that are able to move mountains even when I showed up at her doorstep with a face tattoo in my early 20s.Like Manjushri’s sword of wisdom cutting through ignorance, my obaachan’s unconditional love cuts through my self-consciousness.

The first night in my hometown felt like a ghost world. There were no cars on the road, businesses were closed while the sun was still out, and the usual tourist population was nowhere to be found. The silence was beautiful if you didn’t think about how it got there in the first place. While I was incarcerated, I read a story about a veteran who returns to Monterey after the war. He attends a huge party at a beachside community center meant for surviving soldiers. After a few interactions he notices no one is paying attention to him and he realizes he didn’t actually make it back from the war. Only his spirit returned. The feeling that aroused while I first read this story blanketed the landscape of the small coastal town while my mother, my wife, and I drove around in search of dinner.

We finally found a restaurant open and lo and behold it was a Japanese bento box style joint. No matter what the crisis or how late at night it is, you can always count on a lone Asian restaurant to be open even with a rapidly spreading virus on the loose. We returned to our hotel rooms and ceremoniously devoured root vegetable tempura, yaki udon, inari, chirashi, and teriyaki while listening to the late night growling of harbor seals echo across the bay.

The next morning we planned to drive out to Big Sur so I could film a 1 minute video on my experience as an Asian American in America for a PBS special. The video was going to be included into a larger documentary for Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage month. My mother opted out so she could walk along the beach in solitude. Even before the pandemic my mother had been self- isolating, but the shut-down exacerbated her detachment. Afterwards we met at the Asian Market in Marina before returning to my obaachan’s house .

“Are you depressed?” I asked my mother bluntly between the aisles of dry noodles and soup mixes.

“No, I’m not depressed,” she responded, avoiding my gaze.

“Then why didn’t you take the drive with us down to Big Sur?”

“I didn’t want to be a burden. That’s a nice drive for a couple.”

“You will never be and can never be a burden. Why do you say things like that?”

“Like what?” she said in a low voice.

“Like, you think you’re a burden or ‘that’s a nice drive for a couple.’ As if implying you’re outside of that realm.”

“All I’m saying is that’s a nice drive for someone who has someone, sounds of the market filled the air. “Because I don’t have anyone.”

“Are you out of furikake?” she said after a while. She grabbed one of the flavors off the shelf and put it in her basket.

A little before the pandemic my mother was priced out of her apartment and had to rent a room from her friend on the otherside of the city. Instead of downsizing my mother put everything in the biggest storage unit she could find. My brother and I moved everything for her and I’d be lying if I didn’t say it was exciting to rummage through all the momentos my mother had been hoarding for decades.

“I’m fine. You don’t have to be worried. Anyway, how can I be depressed if I’m not sad all the time?” Her eyes widened as if she thought she had my concern defeated with her argument.

“Depression comes in waves. Sometimes it lasts longer than others but that’s what it does: it just keeps coming.” I took a few breaths. My mother is the only person who can get under my skin.

“Do you ever imagine what it would have been like if we never moved away?” She was now deciding between large sesame crackers or the multi honey cracker bag. “Maybe your dad and I would have stayed together.”

My wife appeared with a full basket and gave the signal that if we stayed any longer we’d need another basket. My mother looked at us and wiped a single strand of silver hair out of her eye. “Be lucky you two have each other. I am all alone.”

“If we become familiar with action and come back to this concrete place, the truth is evident that the myriad dharmas are not self. Firewood becomes ash; it can never go back to being firewood. Nevertheless, we should not take the view that ash is its future and firewood is its past. Remember, firewood abides in the place of firewood in the Dharma. It has a past and it has a future. Although it has a past and a future, the past and the future are cut off. Ash exists in the place of ash in the Dharma. It has a past and it has a future. The firewood, after becoming ash, does not again become firewood. Similarly, human beings, after death, do not live again.”

“If we become familiar with action and come back to this concrete place, the truth is evident that the myriad dharmas are not self. Firewood becomes ash; it can never go back to being firewood. Nevertheless, we should not take the view that ash is its future and firewood is its past. Remember, firewood abides in the place of firewood in the Dharma. It has a past and it has a future. Although it has a past and a future, the past and the future are cut off. Ash exists in the place of ash in the Dharma. It has a past and it has a future. The firewood, after becoming ash, does not again become firewood. Similarly, human beings, after death, do not live again.”

In the second year of the pandemic, I drove to Monterey near the end of May after a backpacking trip in Point Reyes. I was by myself on this trip and wanted to have one-on-one time with my obaachan and watch sumo tournaments with my uncle. We watched Japanese game shows and specials on matcha farms and pottery; kitsugi, golden joinery, the art of repairing broken pottery to represent the beauty in all imperfections and flaws. I couldn’t understand anything except for a few words and gestures here and there, but sitting next to my obaachan was healing. While I wrestled with the language barrier I asked my obaachan if she would travel to Japan with me.

“I wouldn’t even recognize it anymore,” she nearly whispered without taking her gaze away from the rolling fields of green tea plants and palm leaf conical hats.

“But if we go together we can help each other over there,” I replied. “We wouldn’t have to stay in Tokyo. We could go to the countryside and visit your small fishing village in Hokkaido and visit our Buddhist burial site.”

“I am getting so old,” she stammered. This phrase is the phrase I heard repeated ever since I could understand language.

“You look as if you’re still 50.”

She blushed but then a solemn expression covered her face, a terrifying glare.

Without revealing the sentiment to me, I knew she wanted to preserve the memory of her homeland before she moved to America. A country still rebuilding after fire bombs and atomic fumes but before a revolutionized modernization that is now Japan full of bullet trains and skyscrapers. I also am the sole bearer of a world shattering secret my obaachan has told no one else involving an incident on an Okinowa miltary base I could never repeat. The desire for me to visit my ancestral roots is as great as my obaachan’s determination to never step foot there again.

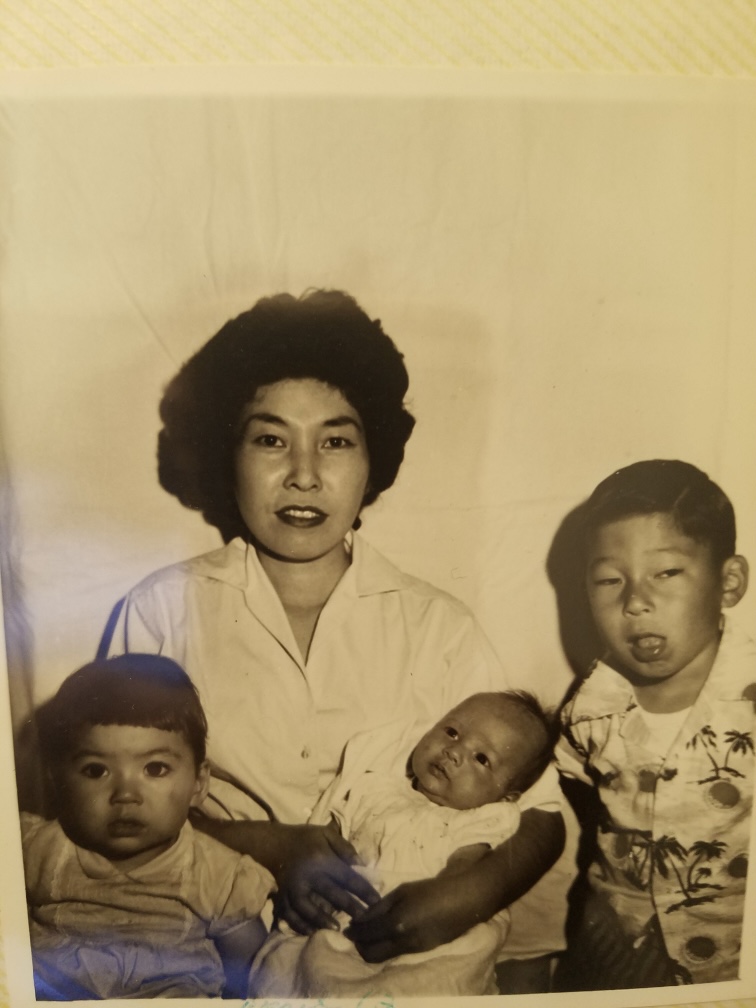

Before dinner, she brought out multiple family albums I had never seen. All black and white. In the background were family houses in the style of nihon kenchiku in Tokyo and Hokkaido. I held photos of my obaachan standing near the Tokyo Bay in a white blouse and dark skirt, my great aunt in front of a Buddhist temple wearing a fur lined coat, and my grandfather sitting in a yakitori bar as an extra in a movie. All of them younger than I am now. There were also photos of my obaachan’s father and her older brother (who I really do resemble). It’s funny how the past can strengthen one’s true self and reattach ancestral roots. The look on my obaachan’s face while we journeyed through her nine decades of memory was the look of a child beneath her first cherry blossom snowstorm.

“What was Hokkaido like growing up? What was living with your brother like after the war began? What was your aunt’s bar in Tokyo like? Is it true your grandfather was a Japanese priest and grandmother a shinto shaman? Who were our Ainu ancestors? Was it hard to move to Tokyo from Hokkaido?” Being mixed is a strenuous line to navigate and those photos reinforced an identity I am constantly in search of, not one given to me by external forces. I was hungry for my history, searching for that umami flavoring of my genealogy.

She never spoke much about the past, or anything other than growing old and if she could drop whatever she was doing to fill our bellies. But this trip was different. My uncle Bill, my mother’s youngest brother, had passed away from alcoholism earlier in the pandemic a few feet from where my obaachan and I sat in the living room. A tragedy she was still grieving. A tragedy we are all still grieving.

“I’m so happy you are here. I am so alone. I have no one to talk to,” her words strangled my esophagus. “Your uncle Tom just comes home from work, eats, and then watches TV in his room.”

“What about my mom, obaachan?” Her eyes widened when I asked this.

“I am grateful for your mom. But she is only here for a short time when she visits,” she paused.

My mother takes care of her when she visits. She would schedule her doctor appointments, make sure she takes her medication, which my obaachan doesn’t enjoy, and takes her shopping and to her hair appointments. But the relationship has flipped, where my mother is the motherly figure and my obaachan the child, something neither of them anticipated. My mother also tries to regulate my obaachan’s nightly sake intake and scolds her self-medication.

“I am going to Japan next year,” I confessed.

Her eyes lit up like floating lanterns. I flipped to a page in the photo album where she was 18 with a full tooth revealing smile and sitting next to her father, who had an equally wide smile.

“The war was awful.” She slowly ran her fingers over the photograph.

“Where were you born in Hokkaido?”

“I was born in Sapporo but that was because it was the nearest hospital. We lived out in the country but then after the war our father sent me to live with my older brother in Tokyo and my other siblings with other family. It was an awful time. The kids were mean there because we were from the country. Then we moved back to Hokkaido and the kids were mean too because they thought we were now city kids.”

“What did you like more, Hokkaido or Tokyo?”

“Tokyo,” when she said it a wide grin stretched across her face and a fond memory appeared. “There was more to do and more family were there because of all the relocations from the war. I liked living with my brother very much.”

“When did you move back to Tokyo?”

“When I was 18,” she released a small laugh. “As soon as I was able to, I moved back with my brother.”

“What was my mother like as a baby?”

“When we were in Germany, she was popular with the neighbors, but not as popular as your uncle.” Again, she released a laugh but this time the gesture was much longer. “One of our neighbors who used to babysit your mom and uncle offered to raise your uncle because she couldn’t have kids. She was obsessed with the Japanese baby.”

“What did you say?”

“I told your grandfather we have to get back to Japan!” She reached out her hand to grasp mine and we both were consumed with laughter.

“Then what happened?”

“We moved to Okinowa.”

“How was that?”

“Awful. Awful.” Her eyes began to swell. “Very very bad men in the military…

I am getting so old…” I swung my arm around her and continued to flip through the family portraits; kimonos, Nikko Kanko Hotel, pagodas, weddings, baby photos and a photo of 40 Sato’s and Miyamoto’s.

“What was I like as a baby?”

“You want to hear a funny story?” She reached out to her water glass and took a small sip. “One night your mother had to go to work and your father never came home. Your mother showed up here when it was dark and asked if I could watch you. I always enjoyed watching you. I put you to bed in uncle Tom’s room and went back to the living room. After a while you got up, didn’t say a word and laid in front of the TV and began to cry. I picked you up and cradled you and you stopped crying. You got up and went to the same spot in front of the TV and began to cry again.” She let out a laugh I had never heard from her before. Tears formed in her eyes as she recounted this memory.

“[The spiritual intelligence] is unrelated to brightness and darkness, because it knows spiritually.We call this “the spiritual intelligence,” we also call it “the true self,” we call it “the basis of awakening,” we call it “original essence,” and we call it “original substance.” Someone who realizes this original essence is said to have returned to eternity and is called a great man who has come back to the truth. After this, he no longer wanders through the cycle of life and death; he experiences and enters the essential ocean where there is neither appearance nor disappearance.”

In 2022, I found myself again in Monterey with my family during May. As the month came to an end, I reflected on the irony that our constant struggle against the dominant culture to stereotype our wide-casted net population and rise of hate crimes against Asian Americans and really all non-white Americans will continue and never cease to end. Our community witnessed the resurgence, but really, just more documented, hostility and violence against us when news broke out of the first case of COVID in China and the closures of the pandemic set in. It felt like every day major news channels were reporting on older Asian women getting punched in the face or brutally attacked in front of people on the subway and the continued racist rhetoric from our elected officials. The more incidents that occurred, the more I felt like I needed to share space with my Japanese family, be in their presence, and come home.

The gravitational pull of my first childhood wave continues to break all these years and keeps me treading along in this dreamlike, illusory realm. My mother took a week’s vacation off of work to stay at my obaachan’s to help run errands and get a reprieve from the late-spring central valley heat. I planned my return from a work trip to coincide with my mother’s vacation. Three generations were back again under one roof. Instead of a tatami mat, I took a nap after arriving in the recliner my Uncle Bill died in facing a glass cabinet that held sacred mementos my obaachan brought with her from Japan: original calligraphy from my great aunt, little Japanese wooden masks and dolls, and a smooth, rounded stone with Bodhidharma’s face painted on it. While my mom made dinner, my uncle and I watched NHK World TV (Yokozuna Terunofuji claimed his seventh Emperor’s Cup at the Summer Grand Sumo Tournament in case you’re wondering).

The next day my mother and I walked along the coastal path of Asilamar Beach, dipped our feet in tide pools, took long drives through neighborhoods of my mother’s teenage years and ate sushi at Ichi Riki, where my mother worked years ago while pregnant with my brother. We also got pedicures in Seaside and drove past the first apartment my mother and her boyfriend moved into after my mother was kicked out of her parent’s house. She told me about the teen center where she, my uncles, and most Asian American kids in the neighborhood would hang out (also where my mom and her boyfriend sold weed). As my mother would rapid-fired these memories while I drove, I realized just how complicated all our identities are. My mother and I have always been an open book for one another, but this trip especially brought us closer.

We ended our day at a Cypress tree at Lover’s Point in Pacific Grove, a wealthy area of Monterey County where my mom worked as a house cleaner when I was a baby. She would take me with her to play with the toys of the children of her clients. Seven years ago when I was released from my last incarceration and treatment center residency , my mother picked me up from Santa Rosa and drove me to Monterey. Okaerinasai, welcome home, meaning returning to the source in Buddhism, like a cuckoo’s song beckons me to come home. We stood there in silence, in awe.

I’ve always struggled with the questions of who I am and what makes me me, and to quiet the constant voice I resorted to injecting drugs and wearing handcuffs. It was easier to drown myself in a false sense of reality in which obsessive opiate intake carries you and to define myself by what judges, law enforcement, medical evaluators and court papers described me as. I was too afraid to engage in the work that actually reveals what I am, what I am not. I am a Japanese Swedish Hungarian/Slovakian French Balkan American felon, educator, poet, and sober heroin addict. I am also my obachaan’s mago, my mother’s son, and I come from a long line of strong independent Japanese women. Today, I am comfortable in the not knowing.

T. William Wallin-Sato is a Japanese American who works with formerly/currently incarcerated individuals in higher education. He is also a freelance journalist covering the criminal justice system through the lens of his own incarcerated experience. He holds an MFA in Creative Writing and was the winner of the Jody Stultz Award for Poetry in the 2020 edition of Toyon Literary Magazine. His first chapbook of poems, Hyouhakusha: Desolate Travels of a Junkie on the Road, was published in 2021 through Cold River Press, and his full manuscript was selected by John Yau for the 2022 Robert Creeley Memorial Award. His work is featured in or due to be released in Cultural Daily, Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine, The Asian American Writers’ Workshop: The Margins, Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, Anti Heroin Chic, and Neon Door. Wallin-Sato’s work comes out of the periphery and supports the uplifting of voices usually spoken in the shadows. All he wants is to see his community’s thoughts, ideas and emotions freely shared and expressed.

Poetry Chapbook: https://coldriverpress.com/HTML/AUTHORS/wallin/wallin.htm

Project Rebound: https://projectrebound.humboldt.edu/